Part two on how to find truth (go here for part 1):

You must build your worldview from scratch. Wouldn’t it be great if at the very base of all your beliefs, at the core of your thought process, there was an impenetrable foundation of certainty? It is possible to construct such a worldview. So, let’s start with statements of which we can be certain their accuracy. Then, we can find out what properties a true statement has.

Statement #1: No unmarried man is married.

Sure, it seems obvious. But what is our justification for believing in such a statement? The answer: logical reasoning. Get ready for methodic thinking. Bear with me.

Now, within this statement, there are definitions which we are giving to certain words. The very definition of “unmarried” means the opposite of being married. Is there a way for this statement to be false, given our definitions? Is there any possible way that an unmarried man can be married? No.

But let’s try to find a statement which would challenge this. What would convince us that an unmarried man could be married? Simple, if it were the case that the following statement could be true: A man exists who is unmarried and married.

Pardon the anticlimax. This is important. Is there any possible way whatsoever that the above statement could be true, even by the wildest of speculations or situations? What about on Mars? Can we be absolutely certain that even on Mars, no unmarried man is married? Yes. We do not need to go out and empirically verify this is true on Mars. It is absolutely true in all possible situations, given the definitions of our terms.

Wow! Truth! Just like that! One might say, “well, that truth is completely useless to me. How does one base a worldview off of the definitions of bachelors?” Good point, but we can now know the possibility for certainty does exist. That is step 1. Perhaps there are other more relevant truths to discover using logical reasoning.

Statement #2: You exist.

Well, perhaps we are only slightly moving up the scale of practical truths. As I briefly alluded to earlier, you can be certain that you exist. Why? What would convince us that we might not exist. Is there room for doubt?

What sentence might convince us that we might not exist? The following statement would do so if it were true : I might not exist (which can only be said to yourself).

If that statement is true, we have reason to doubt our own existence. So, is there any possible way for that to be true? No. Who is asking the questions? When one says “I” anything, that is an absolute affirmation of “I”.

In other words, if “I” did not exist, “I” could not say that “I don’t exist”. You must exist if you have the capacity to say “I”.

This being said, it becomes much more difficult to prove anything beyond this, even that “you” are a human, or that anyone else exists except you. In fact, you might actually be a butterfly dreaming that you are a human (as a Chinese philosopher once pondered). How can you know for certain? Even if this were true, however, “you” would still exist, albeit as an winged insect.

This being said, it becomes much more difficult to prove anything beyond this, even that “you” are a human, or that anyone else exists except you. In fact, you might actually be a butterfly dreaming that you are a human (as a Chinese philosopher once pondered). How can you know for certain? Even if this were true, however, “you” would still exist, albeit as an winged insect.

The fact of your existence is an absolute truth that actually tells you a little something about something! It is not just playing with definitions. That should be incredibly exciting! Absolute truth!

So, those two statements might not have been completely groundbreaking (though they were for me). The takeaway should be this: you can know truth by using logical reasoning. One principle tenant of logic is the following: statements with contradictions can not be true. This can not be overemphasized. Really, it can’t. So, I am going to say it again, with italics, underlined, and emboldened. Statements with internal contradictions can not be true.

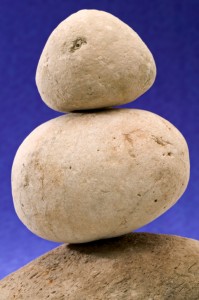

This truth is the most practical of them all. It should be the foundation of an accurate worldview. It can be justified to such a degree that it can not be false. What better cornerstone for a worldview than a statement which applies to all other statements ever to be created and can not be false?

Here is an example of why this is so relevant. Let’s say someone is claiming that it is good for the poorest in our society to see an increase in their standard of living. Because of this, that person concludes the minimum wage is beneficial for the poor’s standard of living.

What would be necessary in order to reject this conclusion? If it could be shown that these propositions actually contradict one another, then we know such belief must be false.

Indeed, for fairly simple reasons, the minimum wage actually hurts the poor (which I will expand upon in the future). In fact, of any group, it harms their standard of living the most.

So, on the one hand there is a belief that the poor’s economic situation is important, and on the other hand there is defense for the minimum wage which hurts the poor’s economic situation. This demands a change in belief in order to avoid contradiction. Either change the feelings about the plight of the poor, or change the beliefs about the minimum wage.

This specific example has consequences not only in the world of ideas. People’s lives are very tangibly impacted by such things as the minimum wage. Economics in general is a field where contradictions are everywhere and with enormous consequences. Fuzzy thinking, especially from those in authority, affects every aspect of peoples’ lives in one way or another.

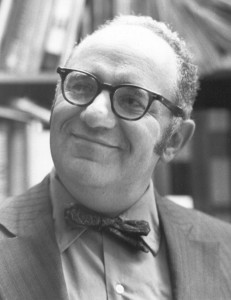

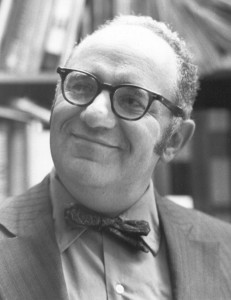

Take a more extreme example, let’s say one believes in the following proposition by Murray Rothbard:

“No one may threaten or commit violence (‘aggress’) against another man’s person or property. Violence may be employed only against the man who commits such violence; that is, only defensively against the aggressive violence of another. In short, no violence may be employed against a nonaggressor.”

Can one belief in this principle and simultaneously justify something like taxation? Taxation, after all, is (within its definition) a threat of imprisonment by force to those who do not pay a determined amount of money to the state. If you don’t pay up, you go to jail, even if you are in no way an ‘aggressor’.

Well then, perhaps we can not believe in such a lofty principle! One of our premises must change. Perhaps only sometimes we believe in this principle, not always. This way, one can believe taxation is justified and still believe that the ‘non-aggression’ principle should be followed most of the time. If that first proposition doesn’t change (if you absolutely defend the non-aggression principle’), something as prevalent around the world as taxation is not justified. What a conclusion that would be!

Either way, you can see the enormous consequences of such reasoning. What could be more practical to everyday lives in society than applying this thought process to something like the government, which affects everyone? Indeed, in a country like the USA, it affects the whole world if we can conclude certain things about the state.

I can say with certainty that logic is the first rock on which to base your worldview if your goal is to find truth and avoid contradiction.