The Preface:

James: I’ve been worrying about my mind, Stanley.

Stanley: Oh no. For what reason?

James: I don’t think it has the power I once thought it did.

Stanley: What do you mean?

James: Well, I used to think my mind was an objective arbiter – that somehow, after listening to an argument, I could determine what was absolutely true or absolutely false.

Stanley: You’ve grown out of this?

James: Indeed. How could it be that my mind could know anything about “absolute” reality? You have to take into context our position as humans. We’re pitiful little creatures who have become adept at navigating our physical world. Our brains have developed to merely aid our survival. Human survival does not depend on black-and-white judgments, but instead accurate probabilities.

If I am looking at this chair, to ask “Does this chair actually exist in reality?” is pointless. All we need to know is, “To the best of my knowledge, does this chair exist, and will it break if I try to use it?”.

After all, how could it be that a creature could ever evolve the capacity to know “absolute” reality anyway? Yes, the complex circuitry in our brains creates incredibly powerful computing-capacity. But how can one make the jump from electric signals in the brain to ultimate arbiter of truth?

Put it this way: our senses give us lots of data about the external world, but our data-set is always changing and expanding. Just because we’ve seen a consistent pattern over a certain amount of time doesn’t mean we then “know” “the truth”. Finite data input can never result in perfect knowledge. I am homo sapien, not homo angelicus.

Stanley: I see your point. Thus you would conclude: with such limitations, it is impossible to know anything about reality with complete certainty.

James: Correct. To think otherwise seems presumptuous.

Stanley: Such skepticism forces you to keep an open mind, does it not?

Stanley: Such skepticism forces you to keep an open mind, does it not?

James: Of course. If you can’t know anything with certainty, one is always open to the idea of being wrong. This results in intellectual humility.

Stanley: Allow me, then, to ask you a few questions. If your argument withstands further skepticism, I, too, will conclude that we are inescapably bound by our finite thinking.

James: By all means.

The Argument:

Stanley: You mentioned this chair earlier. We both believe it exists, but you’d say we can not know, right?

James: Correct. I sense that it exists, but I do not know my senses are accurate.

Stanley: Interesting. But you sense it?

James: My eyes perceive it. But again, I can’t know if it is “objectively” there. It could be a hallucination.

Stanley: You’ve missed my point. Is it true that you have a sensory experience of a chair?

James: Yes, as I have said three times.

Stanley: Is it absolutely, objectively true that you have a sensory experience of a chair?

James: Oh, I see where you are going. Well no, I can’t know such a thing. That presupposes all sorts of things I can’t know.

Stanley: Then let’s go one step further: do you have sensory experience at all?

James: I think so, but I don’t know. I don’t even know “I” exist.

Stanley: We might debate that point, but let’s go one more step. Does perception exist?

James: I don’t know what “exist” means.

Stanley: Fair enough. How about this: in reality, is there such a thing as perception? Regardless of if perception is accurate, and regardless of whether or not “you” exist, tell me, is perception a real phenomenon?

James: Well…

Stanley: Even if nobody else experiences it, and you can’t ever know if your communication of such a phenomenon is possible, think to yourself: does it happen?

James: Yes, I suppose it does.

Stanley: Are you sure?

James: Well, yes, perception is happening to me right now.

Stanley: Are you absolutely certain?

James: That perception is happening? Yes.

Stanley: So, you’re saying that you know something is true about reality with perfect certainty?

James: Well… I don’t know if I would put it that way.

Stanley: If it is the case that perception happens, and you know that perception happens (as you have a direct insight into whether or not it does), it must be the case that perception happens “in reality”. If that is true, then you must know something is true about reality.

James: I can’t really conclude otherwise. The only way to remain skeptical is to doubt whether or not perception exists, and I can not deny that I experience perception.

Stanley: Then perhaps the worry about your mind was misplaced. Your mind must possess the capacity to discern absolute truth from absolute falsehood, as that is what you have just done. This seems like nothing to worry about!

James: But how can my mind do such a thing?

Stanley: I don’t know. That is square two. We were just dealing with square one. Just because we don’t know the how at this moment, doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen. Perhaps we’ll have a future conversation about it.

James: I hope so.

Stanley: There are just a couple things I would like to suggest, in conclusion.

James: Please do.

Stanley: There is no reason to believe we can only discover one truth – that perception is a real phenomenon. All we have to do is deeply analyze why it’s the case we can know things are true or false with certainty. In fact, we might even be able to discover a technique, if you will, for knowing. What conclusions can be known? I’m not sure what the total amount is, but I know many.

But that is a conversation for another time.

Once we have established one truth, others can unfold from it. (If A then B, and so on) What do you suggest for technique? Coherence?

There is the problem of perception. By definition perception exists. To say with honesty, “I perceive,” or for that matter, “I don’t perceive” denotes a truth. But can humans know truth independent of perception? I doubt it. Take math, for example. Math might appear to exist independent of perception, but its most fundamental propositions are dependent on observation. For a person to construct a numerical system requires that person to identify finite objects to count. Even if math can present truth abstractly, the fact that “1 + 1 = 2” is dependent on observation. It is dependent on perception. Much depends on the legitimacy of perception. Our understanding of truth is locked within the confines of that perception.

This is not really a problem for your dialogue, but it is important for technique.

Well, I am not sure exactly what you mean by “coherence”. I would suggest using logical deduction.

As for mathematics being dependent on perception – it depends on what your definition of perception is. If cognition is equated with perception, then yes, I agree with you, mathematics does not stand alone without a subject to “perceive”.

Without a subject, there wouldn’t be “one” or “two” things, there would just be. The mind is what divides up existence into pieces and uses mathematics accordingly. Without such artificial division, mathematics has no use.

There is a critical shortage of inroamftive articles like this.

That’s the best answer of all time! JMHO

Just seeing those tights made my day, they are incredibly amazing. I'm enjoying the mismatched floral here, you've pretty much mastered wearing floral in any which way.

Nice dialogue. I agree on fundamentals.

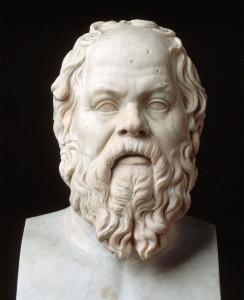

The difficulty with Socratic dialogue is that it can’t address the detail necessary for the really meaningful claims of philosophy. Just like most thought experiments, it’s easy to say something like “Of course I agree that perception (whatever it is) happens,” and conclude, therefore, that you have discovered something upon which to build more philosophy. In reality, you’re not actually proving anything, you’re confirming a shared bias and looseness in language between people.

Imagine you’re talking to an actual skeptic, a brain-in-a-jar or all-life-is-a-computer-simulation person. There’s probably not actually an agreed-upon definition of ‘perception’ here. If I were such a skeptic, I just say “No, I don’t agree that perception is clearly happening, because I don’t know if perception is light rays entering my mind or 1s and 0s in a program altering some code. I don’t even know what “I” is in any meaningful way, so I can’t answer the question.” More frustratingly, the actual skeptic might not even postulate an idea of what “perception” is, so they could never actually agree that such a thing is happening to them.

Of course the more important response might be “Yes, and?” Even if all the definitions above were somehow agreed upon (and I don’t think they can be without making even more far-reaching assumptions), it’s not clear that knowing any one thing means you can know anything else.