Think warm; be warm. Believe in the curative powers of a pill, and watch your body respond. How can it be that mere belief can affect physical reality? The placebo effect is one of the most difficult phenomena to reconcile with nearly any worldview.

If you are sick because of some bacterial infection, it makes perfect sense that ingesting an antibiotic will make the infection better. But how silly does it seem that a simple belief in the effectiveness of a pill, regardless of if that pill is an antibiotic or a sugar pill, will also make an infection better? We’ll look at this problem from three different perspectives.

[Note: By "dualism", I will simply mean the belief that mental phenomena and physical phenomena are fundamentally different.]

Worldview #1: Radical Dualism. First, perhaps the easiest worldview: the placebo effect is a mere example of mind-over-matter. Mental states have the power to override and change physical states. In one sense, the truth value of the statement “I am healthy right now” can be determined by the belief in the statement. If you don’t believe you are healthy, you aren’t. If you do believe you are healthy, you are. “Health” is not a completely objective phenomena, but is dependent on subjective, mental states.

Now, in this worldview, there are a couple of difficulties. First, there is an assertion of free will. (Because if our mental states [beliefs] are determined by previous physical states, the placebo effect is not effective, by definition. They merely become another link in a causal chain.) Defending the existence of free will is already a difficult, radical position to take.

Also, there is difficulty in explaining just how these mental states can affect physical reality. By what mechanism or process can a person choose or believe molecules to act in various ways? Does a belief pop into physical existence for a split second to knock molecules around? How else can it be physically effective?

Finally, where is the line drawn with this worldview? Surely, you can not will yourself to be taller? Or, can you? Just what are the limits of the mind-over-matter phenomena? If we can hold beliefs which change physical reality inside of us, why can’t we ever seem to alter physical reality outside of us (through telepathy or something similar)?

(Keep in mind, a lot of people throughout history have claimed to be able to alter external physical reality through the power of the their mind. To date, none of these claims have help up to scientific scrutiny. This doesn’t mean there are no telepaths, but it sure does seem coincidental that everybody with psychic powers loses their mystical ability when put in a controlled, laboratory setting.)

Worldview #2: Self-Deluded Dualism. There is perhaps a less savory explanation for the placebo effect: we kid ourselves. There needn’t be anything mystical or radical about the placebo effect if it doesn’t really exist. It is not actually the mere belief which changes physical reality. It is physical reality which creates the belief. We don’t need to assert a free will, either. Any beliefs that we hold are completely caused by physical, chemical reality, and our “beliefs” are a result of matter-over-mind.

In fact, you might say something like this: it is predictable that we think we are healthier when we believe we are healthier. Of course… isn’t that self-evident? This doesn’t mean we can actually become healthier by believing so. It just means we are effective at deceiving ourselves.

Now, of course, there is a big problem with this worldview: the evidence suggests otherwise. At least, the evidence overwhelmingly suggests that our beliefs, in fact, do have a causal effect on our well-being. When we think healthy, our bodies seem to react. Chemicals get released by mental states that would not have been released otherwise.

(Of course, one might say that our beliefs are merely caused by previous physical states, to avoid the question of free will, and that makes things easier.)

[And get this, if you deny the existence of the placebo effect, if you don’t believe in it, you won’t experience it. Normally, we need positive evidence of something before belief. However, this suddenly becomes a mistake, and leads to inaccurate conclusions. In this case, you actually need to believe in the placebo effect in order for it to exist, by its nature.

This is why I call the placebo effect terrifying. It is like an example of faith. If you don’t believe God exists, you probably won’t see him anywhere. If you do believe God exists, you will probably see him everywhere. Wouldn’t the skeptical position be the correct one to take? It does not seem so, at least for this phenomenon, and who knows to what else this applies? If you believe leprechauns exist, will you start actually seeing them?]

Worldview #3: Consistent Physicalism.

If we eliminate the distinction between physical and mental, and reduce everything to physical, what should we make of the placebo effect? First, we have to change what we mean by belief. Ultimately, a “belief” can be fully reduced to electric circuits and chemicals. As we will see, there is no room for an effective placebo effect in this worldview.

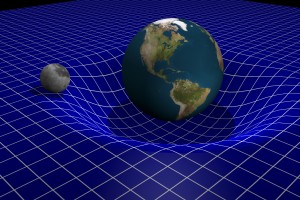

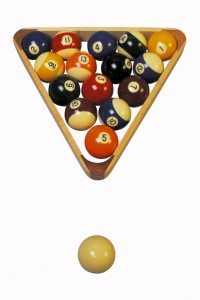

Any given physical state is caused by the physical state preceding it. This means all “beliefs”, as we have defined them, are caused by physical interactions between molecules. This means that a “belief” affects physical reality like a cue ball affects a rack of pool balls, with the cue ball being struck by a cue stick prior (again, this eliminates the need for a free will). Chemicals cause our brain to perceive a “belief”, and chemicals cause our bodies to react. There is nothing mystical involved.

The difficulty in explaining the placebo effect comes from drawing a distinction between physical and non-physical. If no such distinction exists, we don’t need to invoke mind-over-matter nonsense. It simply ends with matter. We can explain the curative powers of “belief” by concluding that the human body has already within it incredible reparative power which is able to be unlocked through certain chemical processes.

Keep in mind, this worldview also has the most compelling explanation for why mind-over-matter psychics are always thwarted: they are selling bunk.

(Of course, a physicalist will have an interesting time explaining why any individual holds a belief of being a psychic. What positive physical function can that possibly serve the brain? Through a series of causal, physical events, a brain has concluded that it has powers which is does not actually possess.)

Now, all three of these worldviews address a few important questions which would do anyone good to think about:

I. Can belief change physical reality?

II. If so, does this mean our future is determined by subjective, changeable variables?

III. If not, does this mean our future is determined by objective, physical reality whose causal chains can never be broken?

I. Do we have free will?

II. If we have free will, and our beliefs can change physical reality, does this mean the human mind is able to freely alter objective reality as he chooses? Really?

III. If humans have such a capacity, what in the world are we? Angels?